| The ten songs on this album were recorded during the actual 1959 Miramichi Folksong Festival, which was extended to four evenings instead of the usual three, in support of the Escuminac Disaster Fund

|

The Miramichi is a great river in northern New Brunswick. Generations have fished in its waters and hunted game in its bordering forests. Its lumber has furnished a livelihood for its inhabitants for two hundred years, as they successively produced pine square timber, sailing ships, long lumber, lathwood, pulpwood, pit props and spoolwood.

The name Miramichi is used to include the whole district, the river and its branches, the river valley, the towns and villages, the seaports and the great forests. People say, I come from Miramichi. I live in Miramichi. Vessels clear for Miramichi, meaning any one of the ports. People go hunting in Miramichi, meaning the woods, and so on.

Miramichi is the oldest place name in Eastern Canada which is still in use. It is probably a Montagnais Indian word, meaning Micmac Land. Alas! since the Montagnais hated the Micmacs, the name also means The Country of the Bad People.

The earliest inhabitants of Miramichi in recorded history were the Micmac Indians. It is not known precisely when white men first visited our shores. Some historians hold a plausible theory that we were Leif Ericson’s Vinland of 1000 A.D. French and Basque fishermen were almost certainly here from very early times, but we first appear in historical records in 1534, when Jacques Cartier sailed by what he described as a triangular bay surrounded with sands, and perhaps landed at Escuminac.

In the 17th century, Miramichi was part of the seigniory of Nicolas Denys, Vicomte de Fronsac, whose Acadian grant extended from Canso to Cap Rosier.

Little is known of the scattered French settlements after the death of Denys and his son Richard. French traders and fishermen visited our shores in the 18th century, but we have no record of their activities.

In 1765, six years after the end of the French regime in Canada, two ambitious Scots, William Davidson and John Cart, received a grant of 100,000 acres at Miramichi, chiefly for the fishing.

Scottish and Irish settlers came to work for Davidson, and after the American Revolution came Loyalists and disbanded soldiers. After the Loyalists, we had immigrants from Britain. There were Scottish shipbuilders from Dumfries, out of work after the Napoleonic Wars, Scots from Ayr, Moray and Inverness. There were waves of Irish when times were bad in the Old Country. Americans came for the lumbering in the 1820’s and some stayed. Besides the immigrants there were scattered Acadian settlers. Some had escaped the Expulsion, and some made their way back after it. Industries on the river were lumbering and fishing, with farming a poor third. From 1790 to 1870 we had the now-lost industry of shipbuilding.

All these people who settled in Miramichi had their own folklore and folk culture, which expressed itself mainly in song. They had brought some very old ballads from Britain and France. The English-speaking settlers also brought contemporary songs, such as the Irish street songs and come-all-ye’s and the so-called goodnight songs heard at Execution Dock when the hanging of a criminal was popular entertainment.

The settlers often made up rhymes about local happenings, which were modelled on the earlier songs, with the same words and phrases and sung to an old tune.

A mixture of old and new songs is still sung in remote country districts. Many of our singers can remember when entertainment in the lumber camps, before the days of radio and television, consisted of songs, dances, fiddle tunes and stories, all given by the woodsmen themselves. But even with the advent of modern ways, it is surprising how much of the folk entertainment has survived. Songs which were sung here a hundred years ago are still sung.

Our Miramichi songs are performed entirely without accompaniment, by one singer alone, as they always have been. They tell a story in a sort of rhythmic chant with no formal tempo. An extra syllable in a line gets an extra note, and bars of three-four and four-four time are mixed together. The pitch is sometimes intentionally altered as the song progresses to heighten the dramatic effect. But still the singer in the old style must not project his personality. The goal is to create a mood, not to show off.

The serious collecting of Miramichi folksongs began with Lord Beaverbrook, who suggested to me some fourteen years ago in 1944 that an effort should be made to save the local songs. Lord Beaverbrook always acts with lightning speed, and almost before I could catch my breath, there was a huge disc-recording machine from England established in a hall in Newcastle, and Stan Cassidy of Fredericton was engaged to make records. Miss Bessie Crocker and I went out on the highways and byways in the country, and gathered in such willing singers as we could find. The Lord Beaverbrook Collection was underway!

This regional collection turned out to be an interesting reflection of Miramichi life from the earliest times to the present day. With Lord Beaverbrook for sponsor it revived interest in our local culture. CKMR, the local radio station, has carried a weekly program of our songs for many years.

In 1958, we inaugurated the Miramichi Folksong Festival, sponsored by the Newcastle Rotary Club and the New Brunswick Travel Bureau, and officially opened by the Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick, J. Leonard O Brien. Ken Homer, the well-known CBC free-lance broadcaster, was Master of Ceremonies. Guest artists in 1959 were Alan Mills, CBC folk-singer, and Sandy Ives of the University of Maine. Judges in the past two years were Dr. Helen Creighton, whose work with folksongs and folklore is outstanding, Dr. Carmen Roy of the National Museum of Canada, Dr. George MacBeath of the New Brunswick Museum, Alan Mills, Sandy Ives, and Harry Brown, a local lumberman.

For the festival, singers come from the four corners of Northumberland County and from Gloucester, Kent and Albert Counties. The singing lasts for three evenings. Except for our occasional guest artist, it is a non-professional get-together for the singers and their friends. What we have achieved in the folksong collecting and in the festival is the preservation of a segment of folk culture, an echo of New Brunswick’s past.

The ten songs on this album represent a mere morsel of the wealth of our folksongs. They were recorded during the actual festival of 1959, which was extended to four evenings instead of the usual three, in order to support the Escuminac Disaster Fund. About 25 traditional singers took part in the festival and contributed, in all, nearly 100 songs.

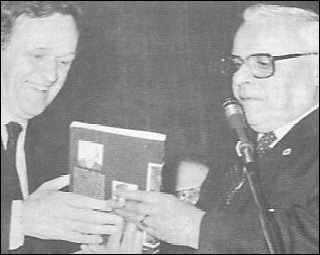

The quality of the singing and of the recording may not come up to professional standards, but the packed and appreciative audiences on each of the four evenings were testimony to the love our people have for their traditional songs, as well as to their admiration of the singers. Liberal leadership contender Jean Chrétien received a copy of Songs of Miramichi when he dropped by Friday Night’s Bicentennial Live Recording session. He received the book from Newcastle Mayor John Creaghan who delighted the audience when he unexpectedly sang a couple of verses from ‘The Jones Boys.’ Miramichi Leader, April 11, 1984